Learning Urdu is akin to time travel. The learner — otherwise seldom in contact with Urdu-speaking environments — suddenly finds herself transported to the gleeful streets of the 13th and 14th century Nizammudin or to the gloom of 19th century Old Delhi following the fall of the Mughal empire, when the fate of Urdu speakers was uncertain.

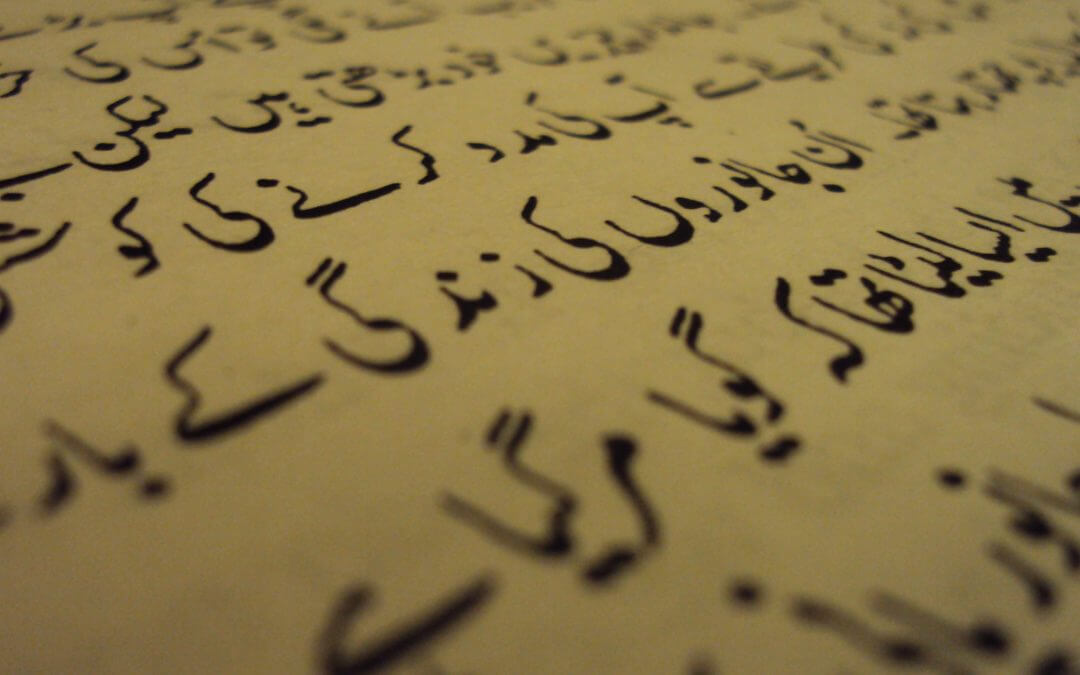

In the process of learning Urdu, one can intuitively sense the transformations the language has undergone through various time periods: from the playful beginnings of a linguistic amalgamation rife with idiosyncrasies that were the subject of riddles and puns, to its maturity as a language of high culture and literature, until its ultimate slow retreat found in what has become New Delhi. Struggling to read a page of calligraphy, the mind experiences emotions that seem to correspond with this journey through time: the initial exhilaration followed by an overpowering sense of gloom or even despair.

Learning to read a new script is always a challenge. But in the case of Urdu, even more so. With a form so malleable that it often succumbs to the whims of writers, calligraphers, and even painters, Nastaliq, as the script is called, is difficult to grasp for beginners. When I picked up my first book to learn the script eight years ago, I felt clueless. And for three years I remained disoriented until I fell upon the Urdu Script Course at Zabaan Language Institute.

The alphabet is set out on the board, connections to their sounds are made, and students are armed with rich new vocabulary and knowledge about ‘full, initial, medial, final forms’, diacritic marks, and other orthographic details. The tracks are laid and the train to Urdu literacy is set in motion. Before long, the destination that earlier seemed unattainable is now visible — and indeed is reached in just a few hours.

Zabaan has been teaching Hindi, Urdu and many other Indian languages for over seven years in New Delhi. Zabaan’s Urdu script course attracts many students who, like myself, feel a connection to the language. Ultimately, these students become explorers fascinated by the culture and literature of the language, looking to catch a glimpse of what it must have been like to walk past Ballimaran and peer through the door of Ghalib’s haveli or to attend a mushairah organised by the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar.

Ghalib Institute in New Delhi

Diorama of the last mushairah

I recently had one such experience at the Ghalib Institute in Central Delhi. This stately ochre building houses a beautiful diorama depicting a scene of the last mushairah in progress at the Red Fort before the mutiny. These lifelike figures, accompanied by an audio recording of the recitation of shayari in the background, leave a powerful impression indeed.

Ghalib depicted in the Diorama at Ghalib Institute

Ghalib, as sculpted in the diorama, seems to be making a very important literary and philosophical point with his hand poised mid-air, his head tilted to one side, and his eyes focused on the object of his thought. Perhaps this thought derives from a feeling that slowly morphs into an image in his mind, which he then visualises in the space before him before translating it into words. And somehow, the words emerging from Ghalib’s mouth are in perfect form and pitch. As he said himself, probably in jest or reflection, “While there are many other poets indeed, Ghalib is unique among them because of the way in which he expresses himself.” Not many would have disagreed then, and very few would disagree now.

Ghalib with his student Munshi Hargopal Tufta

Ghalib belonged to an age in which poetry was not an individual quest for truth or meaning, but rather an art with its own styles, techniques and vocabulary, practiced alongside peers. What is more, aspiring poets were trained to write good poetry, something that is counterintuitive to the spontaneity of thought and feeling that we celebrate in today’s poetry. A teacher himself, Ghalib is depicted at the Ghalib Institute with his student Munshi Hargopal Tufta, a name that should ring a bell to anyone who has attempted to read the collected volumes of Ghalib’s letters.

The works of Ghalib and many other writers fill the library of the Ghalib Institute. The staff is friendly and helpful and the time traveller feels right at home. What better venue for the next batch of Zabaan’s Urdu Script Course starting on 5 November? Anyone interested in the Urdu language and its literature is encouraged to join the course.

Read more by Zabaan:

Senior Advocate Sidharth Luthra Reclaims His Multilingual Heritage

The works of Ghalib and many other writers fill the library of the Ghalib Institute. The staff is friendly and helpful and the time traveller feels right at home. What better venue for the next batch of Zabaan’s Urdu Script Course starting on 5 November? Anyone interested in the Urdu language and its literature is encouraged to join the course.

A teacher himself, Ghalib is depicted at the Ghalib Institute with his student Munshi Hargopal Tufta, a name that should ring a bell to anyone who has attempted to read the collected volumes of Ghalib’s letters.

This was an interesting article. It has some good information about the language learning process. Please add more such articles. Thank you!

I have a word in nashtalik script inscribed on an item and need to translate it. Can you help me? I shall be thankful for the help extended and pay the fees if any.

Sure. You can email an image of it to us at learn@zabaan.com.